Over the coming weeks and months, the United States Studies Centre will bring you a new series of research briefs and reports titled COVID-19: The Big Questions.

COVID-19 is impacting all of us, changing the way we work and interact with one another. This is as true for the USSC as any other workplace.

COVID-19 is not only a pandemic but presents a whole-of-society impact for both the United States and Australia at a magnitude last seen in World War II.

But the work of the Centre goes on. The Centre’s analysis and commentary — its quality and quantity — isn’t being diminished. In fact, just the opposite.

These times dramatically demonstrate the value of the Centre’s mission.

COVID-19 is not only a pandemic but presents a whole-of-society impact for both the United States and Australia at a magnitude last seen in World War II. Both Australia and the US are wealthy, democratic countries, with deep scientific expertise and institutional and cultural commitments to freedom and liberty. Both are federal systems with overlapping and competing centres of power and responsibility, whose public and private institutions are being profoundly challenged by the pandemic. In short, how the US is responding to COVID-19 carries vital points of comparison and contrast for Australia.

Novel virus, persistent challenges: Australian and American responses to COVID-19 compared

The motto of the USSC is “analysis of America, insight for Australia”. You’ll see us providing that insight every day in this forum.

Here we will be drawing together the analysis and insights of the Centre’s researchers and experts, academics, non-resident fellows and its broad network of colleagues and friends in the United States. From the public health crisis itself, to policy and political responses, to the implications for the two nations’ economies, for foreign policy, defence, geo-strategy, and technology, we will be using this forum to bring you rigorous, independent analysis that advances the Australian conversation and Australia’s national interests.

The following contributions from our resident and non-resident experts represents just a preview of some of the crucial work the United States Studies Centre will undertake as we move through these challenging times.

— Professor Simon Jackman, United States Studies Centre CEO

Dr Stephen Kirchner | Director, Trade and Investment Program

It’d be a mistake to shut financial markets: more than ever, we need them to work

"The extreme volatility and losses seen in stock markets in recent weeks has seen calls for financial markets to be closed and short selling restricted. Amid the volatility, it would be tempting to close financial markets, in particular, stock exchanges.

But shutting them down would be a mistake. Keeping markets open will be a painful experience for many, but financial market prices convey much-needed information. Closing them is the equivalent of shooting the messenger.

Stock markets have their own circuit breakers that kick in during extreme volatility, but to do more than that would be to deprive traders and policymakers of the insights they offer. We need prices for financial products in the same way we need prices for goods and services. Without them, decision-making becomes difficult, if not impossible.

Eventually, they will signal better times ahead and give business the confidence to move forward with the recovery."

Claire McFarland | Director, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program

US and China: Tech giants’ COVID-19 response

"Entrepreneurial spirit will come to the fore. As Plato said, necessity is the mother of invention. The United States' global financial crisis caused a ‘Great Recession’ which showed that while a large number of small businesses struggled and failed, many new businesses were successfully created. Indeed, as the unemployment rate increased, so too did the rate of entrepreneurship.

Innovation will be more important as the world deals with and emerges from this crisis. Firms that can commercialise a radically new product or service have the opportunity to dominate a changed world market.

There will be an enormous shift to digital. While our best response now is isolation, our economies are more global than ever before. Digital technologies will keep us connected and drive new growth."

Ashley Townshend | Director, Foreign Policy and Defence Program

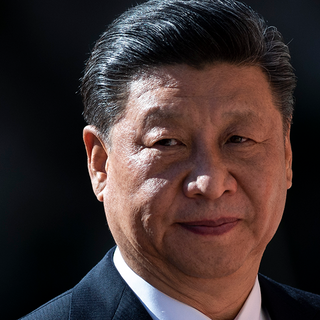

"COVID-19 and the pandemic response is accelerating changes to the distribution of great power influence. The United States, which until recently would have led the international fight, is missing in action and deeply unprepared to deal with infections at home. A combination of political dysfunction and years of cutting back on government has undermined the capacity of US leaders to combat the health, economic, social and industrial disruptions underway. This is damaging the appeal of the United States' political-economic model and power to lead by example.

China, in contrast, is moving fast to fill the leadership vacuum. Despite its culpability and cover-ups at the start of the pandemic, Beijing is now exporting the lessons of its iron-willed response and much-needed testing kits, ventilators and protective equipment worldwide. This action on global health is welcome. But it’s a harbinger of new patterns of influence that will outlast this crisis and define the world that re-emerges."

Elliott Brennan | Research Associate

"Politics-first is a great way to win and hold power in times of safety and times of plenty. Politicising budgets, welfare, health and immigration cultivates fears and mutes the whispers of those better angels of our nature. When a novel crisis collides with this infrastructure of leadership, its political scaffolding lacks the expertise to withstand apolitical forces.

When the COVID-19 crisis starts to end, developed nations like Australia and the United States need to to cauterize the flow of political appointments in the bureaucracy. Slow-walking testing or insisting on attending crowded events on political advice and for the purpose of optics is unacceptable when the health and well-being of a nation is at stake.

In the United States, the political nature of White House appointments during the Trump administration meant that one third of the coronavirus response team exposed themselves to the virus by attending the Conservative Political Action Committee conference. Genuine experts would have cancelled it."

Dr Charles Edel | Senior Fellow

"The long-term effects of coronavirus will be based, at least partially, on its severity and duration — both of which are unknown.

On the foreign policy front, there are several implications.

The pandemic has already revealed shortages in critical life-supporting goods and materials and, over the long-term, is likely to increase calls for more domestic manufacturing capacity and greater domestic resilience. And while global pandemics previously have been areas of cooperation between the United States and China, actions by both Beijing and Washington are accelerating competition between the two powers, marking global health as yet another area of great power competition.

Finally, this could serve as a reminder of the United States’ global role. And that the pursuit of narrow national interest will likely leave the United States less safe, less prepared to lead, and less able to muster an appropriate — or even adequate — response.

Dr Gorana Grgic | Lecturer in US Politics and Foreign Policy

"Amidst the grim news about the severity of this pandemic and its knock-on effects, it is hard to see any silver linings. If there are any, they are the everyday acts of kindness we hear about, along with a glimpse into a world with a significantly lower carbon footprint. Beyond that, COVID-19 is an amplifier of the existing and worrying trends in world politics, such as the resurgence of nationalism, escalating great power competition and the decline of multilateralism.

The public (dis)trust in institutions is also spotlighted as the competence of leaders around the world is tested, and as many people are being led astray in the fragmented and polarised media ecosystem. Ultimately, this global health crisis poses crucial questions about the role and power of the government.

In the US context, it has reignited the healthcare debate, challenged the economic orthodoxy, and raised worries over the potential precedent on curbing civil liberties."

Jared Mondschein | Senior Advisor

"Who are making the key policies about this pandemic and what types of decisions are being made? The World Health Organization, United Nations, G7 and G20 have all issued statements and guidance but bilateral and multilateral discussions are seemingly less relevant than ever. Ultimately, strictly domestic conversations have taken prominence. We are seeing an inward gaze like never before in recent history.

At the same time, the breadth of policy changes is also remarkable. Crises often lead to rule bending and law changing – we all do things in emergencies we would never normally do – but the policy changes are hard to overstate. While federal governments are seemingly expanding their power and roles in countless ways, they are also removing regulatory barriers in everything from occupational licensing to the roles of private medical labs.

My question: How relevant will old conversations and policies be when this ends?"

Associate Professor Brendon O'Connor | Associate Professor in American Politics

Coronavirus may end up being a major player in the US presidential election

"We should choose politicians we think will handle national emergencies and crises well. We certainly punish them if they don’t.

George W. Bush’s popularity never recovered from his incompetent response to Hurricane Katrina (and his administration’s poor planning for such a possible natural disaster). Governing a nation is a serious responsibility; whereas President Donald Trump’s conservative shock-jock approach to his role constantly flouts that responsibility.

One of Hillary Clinton’s best attack lines against Trump was he was not fit to be America’s leader in a crisis. She was right and Americans will suffer because this obvious reality was ignored by millions of voters.

Trump's response to COVID-19 has been classic Trump: ill-considered and self-congratulatory. Despite the very low rates of testing in the US, the president never tires of saying what an outstanding job he is doing. The key question is: will his loyal supporters tire of Trump’s incompetence if they feel exposed by it?"

Dr David Smith | Senior Lecturer in American Politics and Foreign Policy

"Many of the United States' problems look similar to our own — confused public health messaging, states at odds with the federal government and with each other, and a population not taking it completely seriously. The big difference is in testing.

Even though Australia has similarly rigid criteria for testing as the United States, it tested far more people who met those criteria from the outset, and the positive rate is less than 1 per cent. In absolute numbers, the United States is only just surpassing Australia in testing now, and it has a terrifyingly high positive rate of around 13 per cent.

No matter how often Trump calls it "the China virus", it was his administration's early weakness and complacency that allowed the virus to spread undetected through American communities."

Matilda Steward | Research Associate, Foreign Policy and Defence Program

"As Republicans and Democrats struggle to reach agreement on a COVID-19 stimulus package, it’s worth reflecting on an increasingly rare example of bipartisan consensus among lawmakers.

The United States provides significant financial support for international efforts to strengthen pandemic preparedness. While this funding has always waxed and waned, the Trump administration has consistently proposed deep cuts to the United States' foreign assistance budget that contributes to these global health security programs. Each year, Congress has united to protect funding for agencies such as the US Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – regularly appropriating levels up to thirty percent higher than the president’s budget request.

The devastating domestic and international impact of COVID-19 should reinforce the important advocacy function that a unified legislature can achieve."

Brendan Thomas-Noone | Research Fellow, Foreign Policy and Defence Program

"Governments, businesses and citizens all over the world are turning to technology as a quick way to adapt to – and potentially cure – the COVID-19 pandemic. In an amazingly short period of time, theoretical applications of new technologies are being applied in the real world, from hospitals and research laboratories to enforcing quarantine measures and innovating new life-saving medical devices.

We will see significant technological change over the next 12 months or more. As if it was a war, institutions will spend huge amounts of time, resources and capital fighting the virus, both in healthcare spending and research, but also in tracking populations, crunching big data for patterns and innovating new ways to work from home. Our already rapidly changing relationship with technology is only set to gain pace.

But technology isn’t the swift fix some may be hoping for and has its downsides. There isn’t a technological silver bullet to defeating a pandemic, just tried and tested methods."

V. Kim Hoggard | Non-Resident Fellow

"The ramifications of the Trump administration’s ideology of isolation, distrust of government expertise, “deconstruction of the administrative state” and “deep state” suspicions has left a weakened executive branch scrambling to address this escalating crisis.

By leaving key government positions empty, this White House has glaringly exposed its thin management ability to provide the necessary leadership. State governors have stepped up to fill the void. Trump’s early inaction has been a missed opportunity to build trust and confidence, both in the United States and globally.

The pandemic is beyond any “October Surprise” the presidential candidates could envisage. COVID-19 and the accompanying economic crisis are overwhelming the electoral agenda. Voters will be electing a president who can put politics aside, unify the nation and offer a vision for a revitalised American economy with 21st century opportunities that transitions the nation to new social and economic ways of living and recognises the interconnectedness of inequity, climate change and globalisation."

Dr John Lee | Non-Resident Senior Fellow

Coronavirus: No amount of censorship can stop the China debate

"An American conversation about disentangling supply chains from China was already occurring before the onset of the pandemic. Previously, that conversation was largely occurring within the Washington DC beltway and was being applied mainly to strategic technologies such as 5G and critical minerals such as rare-earths elements. COVID-19 has focused more attention on a broader range of goods dependent on China such as antibiotics and other medicines.

This conversation will grow in intensity and importance. Given better appreciation of the risks of relying too heavily on one country, businesses are considering diversifying away from Chinese supply chains as a risk management practice rather than disentanglement from those supply chains which is more driven by strategic and political motivations.

Even so, the growing willingness of business communities to bear the costs and disruption of diversification will provide stronger grounds for American policy makers to accelerate supply chain disentanglement with China."

Stephen Loosley | Non-Resident Senior Fellow

"Populism under pressure is not pretty. The era of big government has returned."

Professor Megan H. Mackenzie | Non-Resident Fellow

"It’s essential to pay attention to the gendered nature of the implications of COVID-19. Women seem to be over-represented in jobs likely to be cut and jobs that put workers at risk to exposure to COVID-19. For example, 91 per cent of the nurses on the frontline of COVID-19 are women; the majority of teachers who have remained in schools and face high levels of exposure to the virus are women (including 97 per cent of primary teachers and 67 per cent of secondary teachers).

Women also make up the majority of the casual labour force, which are the jobs most likely to be cut first as the economy goes into free fall. Given the statistics on division of domestic and emotional labour, women are more likely to face extra burdens — practically and emotionally — from COVID-19.

Finally, police and support services have noted that isolation and social distancing measures put women and children at risk in a country with one of the highest domestic violence rates in the OECD."

Bruce Wolpe | Non-Resident Senior Fellow

"There are two profound implications from COVID-19 for the US political system.

Firstly, Can the United States virulent hyper-partisanship be surmounted to rescue the country and its economic future? The most recent response to a crisis of this order of magnitude — the Obama stimulus to counter the GFC in 2008-9 — saw a huge decline in bipartisanship in Congress compared to the unity of purpose and economic recovery program following the catastrophic 9/11 attacks in 2001. As the United States faces a depression, can Washington work? And can this destructive trajectory be reversed?

Secondly, to what extent will this election year be disrupted? What about the completion of the primaries, holding the conventions, campaigning and voting? Will the November election be conducted with legitimacy and ensure full access to the polls if the pandemic prevents orderly physical voting on election day? Will there be a fair election on November 3, with the results honoured and accepted by all?"